Introduction

Pain is an unpleasant, subjective feeling registered in the post-central gyrus of cerebral cortex as a response to tissue damaging in the organism or to functional changes in some parts of CNS1. Also, pain is one of the commonest subjective symptoms, and the patient’s statement is the only proof to the doctor that the patient is experiencing pain2.

Knowing the methods of measuring the intensity and quality of pain (objective measurement) has great importance for the study of pain as a separate phenomenon. The objective measurement of pain is applied in: diagnostic procedures, determining the therapy for acute postsurgical pain, as well as the therapy for chronic pain, testing different anti-inflammatory drugs (especially analgesics), etc3,4.

The level of sensitivity to painful stimuli is not the same in all persons, and it can be defined as1

- Normalgesia – normal sensitivity to pain,

- Hyperalgesia – increased sensitivity to pain,

- Hypoalgesia – reduced sensitivity to pain,

- Analgesia – complete insensitivity to pain, but with retained feelings to touch and pressure,

- Sensibilization – increased sensitivity of receptors to pain, or lowering the pain threshold of receptors.

Pain is transmitted from the facial area and the jaw through the trigeminal nerve to celebral cortex, which plays an important role in the interpretation of the quality of pain. The perception of pain can also be one of the functions of lower centres; sight, hearing and thinking also participate in the formation of the perception of pain5. Besides, the limbic system modulates the response to pain, as well as hypothalamus, which is responsible for responses of the endocrine system. That is the reason why pain is often accompanied by a series of psychological, bodily and vegetative responses, such as: fear, crying, nausea, vomiting, paleness, etc6.

The objective measurement of pain is determined solely by the patient or examinee, since that right belongs only to the one who subjectively experiences pain. The doctor can systematize and process obtained data using some of the methods of objective measurement, and draw corresponding conclusions based on the data7.

Since individual aspects of the objective measurement of pain (either the intensity or the quality) are mostly described in literature, this paper will present the most commonly applied methods of the objective measurement of pain (clinical pain, in particular), as well as certain results of some of the methods of the objective measurement of pain, based on the studies of both other authors and our own.

I EXPERIMENTAL METHODS OF THE OBJECTIVE MEASUREMENT OF PAIN

The experimental research of the intensity of pain is mostly done in pharmacological studies, especially with the aim of testing new analgesics. The results of these studies are equally significant for theoretical and clinical knowledge in the area of the objective measurement of pain8,9 It must be stressed that there is a significant difference in the measuring of pain in clinical and experimental conditions10. It is much easier to measure experimental pain, since the intensity of the stimulus can be adjusted and measured, while it is impossible to measure the intensity of the stimulus causing pathological pain. Also, in clinical conditions, the gravity of the disease does not often correspond to the intensity of pain, which is modified by different individual factors, such as the pain threshold6. In laboratory conditions it is only the intensity of pain that is measured, and various stimuli (mechanical, electric, or thermal) are used to incite a painful condition. Experiments are done on people, who have previously agreed to that and whose overall state of health is taken care of, or on experimental animals8,9. In connection with the intensity of the stimulus, the measuring of pain intensity can be done in two ways: by the subjective response of the examinee (subjective expression), or by the objective neuro-physiological method of evoked potentials11. In the subjective expression, the measuring of sensitivity to stimuli are described on two levels of response or pain thresholds: one, when stimuli reach certain level in intensity and quality and cause pain; and the other, the level of the pain threshold, when by gradual increase in the intensity of the stimuli, the examinee registers such a severe pain that they cannot bear it1. The method of evoked potentials is, undoubtedly, one of the most precise ways of the objective measurement of pain intensity in experimental conditions. It is based on registering electronic changes appearing in some parts of the brain as a result of the stimulation of senses, receptors or a specific spot on the sensory pathway. Besides, evoked potentials can be successfully applied as a diagnostic and therapeutic guide in patients with a chronic pain syndrome and in clinical conditions11.

II CLINICAL METHODS OF THE OBJECTIVE MEASUREMENT OF PAIN

A. MEASURING THE INTENSITY OF PAIN

Different models are used for the study of pain intensity in clinical conditions; surgical extraction of lower impacted molars is one of the most frequently used methods since it is almost always accompanied by postsurgical pain6. Beside this model, as models of studying the intensity of pain in orofacial surgery, some routine surgical procedures such as: surgical extraction of remaining roots, apicotomy of the tooth root, correction of the alveolar ridge of the upper and lower jaw, cystectomy, surgical correction of soft tissues of the oral cavity, etc12,13,14 are used . The methods of objective, clinical measuring of pain include:

1.Quality scale

This is one of the first recorded methods in which the examinee reports on whether they feel pain or not, disregarding its intensity7.

2.Descriptive or simple scale for measuring pain

This method consists of 4 degrees: slight pain, moderate pain, severe pain, and agonizing pain. A drawback of this method is that patients have few possibilities to determine the intensity of pain; therefore, it is difficult for them to precisely define the pain they feel. Also, the forth degree is almost never selected by examinees15.

3.Method of the verbal description of pain (Verbal rating scale – VRS)

The descriptive scale for measuring pain has been modified in time, by adding a number of terms (5 – 7 or more terms), to the so-called method of the verbal assessment of pain. In this way, the examinee is asked to assess the intensity of their pain by selecting a term. There are usually five points on the grading scale, and those are: painless, slight pain, moderate pain, severe pain and unbearable pain.

The terms can be presented on a scale marked with numbers so that the results can be easily processed statistically; then this method is called the numerical scale. Sometimes this scale can contain more than five terms so that the patient can determine the intensity of the present pain more precisely. A drawback of this method is that examinees can understand one and the same term in different ways; thus, what is for someone, for example, a moderate pain, can be a slight pain for someone else, etc16,17.

4.Visual analogue scale (VAS)

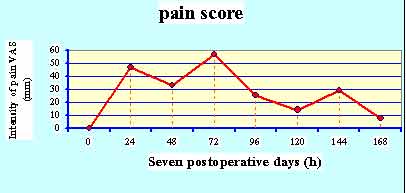

For this method we use a 100 mm-long horizontally drawn line, with one end signifying a state with no pain, and the other end signifying unbearable pain (Fig. 1). The examinee is asked to mark the intensity of their pain on the scale. Then, the length of the line is measured in millimeters with a ruler, and that is the intensity of the patient’s pain at the moment of measuring. This procedure is repeated at intervals to obtain the profile of the intensity of pain (pain score) over a specific period of time (Figure 2)4.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Graph 2: Pain score after extraction of lower third molar |

Although this method seems to be simple, it

is difficult to use in confused and old patients, just as it is

difficult to explain it to some patients. Also, similarly to the VRS,

this one can also be rather subjective, especially if the patient wants

to draw the doctor’s attention by giving false data3,14,18,19,20.

As for the length of the scale (lines from 50 mm to 200 mm have been used), the 100 mm line has proved to be the most appropriate. It is best to mark the latter ending of the line with the words “the worst pain imaginable”19.

5.Method of the graphic assessment of pain (Graphic Rating Scale – GRS)

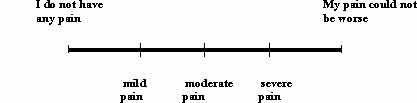

This method is practically a combination of the previous two methods. It is similar to the visual analogue scale – a difference being that on the 100 mm-long line, between the extreme terms (“no pain” and “unbearable pain”), the following terms have been marked: slight, moderate and sharp (Figure 3)21.

|

|

Figure 2: Graphic Rating Scale – GRS |

6.Indirect methods of measuring pain

They are based on measuring some parameters such as: the intensity of catecholamines in urine, pulse, blood pressure, the level of the vital capacity, locomotory functions, the number of analgesics taken, the level of serum beta lipoproteins and cholesterol, etc. The intensity of pain is determined on the basis of the results obtained. All indirect methods are rather unreliable since the assessment of pain intensity is based on measuring parameters other than pain itself7,16. At the Deparment of Oral Surgery Clinic of Dentistry at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Niš, a few researches were done between 1998 and 2002, in which the intensity of pain was objectively measured in over 1000 examinees. In the greatest number of studies, the extraction of lower impacted molars was used as a model of measuring pain; of the methods of the objective measurement of the intensity of pain, VAS, SRS and GRS were applied. These methods proved to be simplest to apply since the application and purpose of the method of the objective measurement of pain could easily be explained to examinees12,13,14. Comparing the results of pain intensity obtained through VAS, VRS and GRS, we noticed no significant differences4,13.

B. MEASURING THE QUALITY OF PAIN

The quality of pain represents a subjective interpretation of the perception of pain. According to the clinical experience, most patients experience pain as: nagging, burning, throbbing, gripping, boring, etc. These differences in the subjective perception of pain depend on numerous factors, such as: types of receptors and their distribution, the nature of the stimulus or damage of the tissue (mechanical, physical, chemical), pathways for the transmission of the impulses of pain, the duration of painful impulses, etc22. To determine the quality of pain, the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) is generally used today. It is a verbal test used to determine more precisely not only the intensity of pain, but also its nature10,15. In the first part of the MPQ, the patient is shown 20 sets of words and asked to select one word from each set, the one which describes the quality of the present pain in the best way. Each set of words contains a few subsets: one is related to the sensory qualities of pain regarding its duration, distribution, the area affected, as well as the feeling of pressure and heat; another set of words in this part of the questionnaire is made up of words which describe the intensity of the overall experience of pain; still another set contains words which mark negative (affective) qualities of pain such as: tension, fear, etc. Part II of the questionnaire contains the degrees of pain intensity, corresponding to each previously selected quality (term) from the related sets and subsets of words; it contains a numerical scale from 0 (no pain) to 5 (unbearable pain).

In this way we can determine:

- The Pain Rating Index (PRI), which represents the total obtained on the basis of selected words in each set and subset. Therefore, the index can be determined individually for: sensory qualities, intensity of the overall experience of pain and affective qualities of pain; and

- The Present Pain Intensity Index (PPI), which is graded on the scale from 0 to 5 (1- mild pain, 2 – unpleasant pain, 3 – intense pain, 4 – very intense pain, 5 – unbearable pain).

The advantage of this method is that it presents both the quality and intensity of pain. A disadvantage is that, in comparison with the VAS and VRS, it demands much time on the part of the examinee to assess their pain. Also, there are differences in expression in certain cultural, socio-economic and educational categories. That is why the questionnaire has been translated into several languages and adapted to different categories of examinees15. Compared with the VAS method, the MPQ method offers more precise data on pain18. The results of the research on pain obtained in this way have shown that pain has the greatest intensity during the night after the surgery of impacted lower third molars, and that the intensity of pain decreases in the following two days23.

C. RYLE’S QUESTIONS

In order for the patient to be able to completely describe the experience of pain and in order to obtain a complete objective measurement of pain, so-called Ryle’s questions5 are usually used in clinical work. These questions refer to:

1. Location of pain,

2. Radiation, as well as where pain radiates,

3. Character of pain,

4. ntensity of pain,

5. Duration of pain,

6. Periodism and frequency of pain,

7. Aggravating factors (change in temperature, in locomotory functions,

spontaneous appearance of pain, etc),

8. Relieving factors (spontaneous disappearance, use of analgesics,

etc), and

9. Potential existence of other changes (anxiety, fear, insomnia, poor

working capacities, etc).

Conclusion

Pain affects the subjective mood in a more perceptive way than any other experience. For that reason, it is necessary to measure both the intensity and quality of pain objectively, in order both to achieve a more humane approach to patients who experience pain, and to apply an adequate therapy which will ease their suffering. It should be stressed that it is difficult to determine the most appropriate method of the objective measurement of pain for routine clinical work, although the advantage is given to the VAS and VRS methods, which, due to their simplicity and easy application, are widely used both in clinical work and in scientific research.

Literature

- Bond M.R.: The nature of pain u Bond M.R.: Pain, its nature, analysis and treatment. II ed. Churchill Livingston, Edinburgh, 1984, pp. 13-54.

- Frohich E.D.: Patofiziologija-poremećaji regulacionih mehanizama u organizmu. Institut za stručno usavršavanje i specijalizaciju zdravstvenih radnika, Beograd, 1982. pp. 167-201.

- Habib S., Matthews R.W., Scully C., Levers B.G.H., Shepherd J.P.: A study of the comparative efficacy of four common analgesics in the control of postsurgical dental pain. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol., 1990; 70: 559-563.

- Kućer Z., Todorović Lj., Burić N., Pešić Z.: Preoperative use of dexamethasone and diclofenac for the prevention of pain and swelling after removal of impacted lower third molars. 4th Congress of the Balkan Stomatological Society, 1999; Istambul. Proceeding of BaSS: 58.

- Dudley H.A.F.: Pain u Dudley H.A.F.: Scott An aid to clinical surgery.Third edition. Churchil Livingstone, Edinburgh, London, Melbourne and New York, 1984, pp. 1-3.

- Nřrholt S.E.: Use of dental pain model in pharmacological research and development of a comparable animal model. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., 1998; 27: 1-41.

- Huskisson E.C.: Measurment of pain. The Lancet, 1974; ii: 1127-1131.

- Cawson R.A.: Analgesics and addiction; u Cawson R.A., Spector R.G.: Clinical pharmacology in dentistry. Forth edition. Churchil Livingston, Edinburgh, 1985, pp. 157-319.

- Hardman J., Gilman A., Insel P.A., Schimmer B.P.: Analgesic - antipiretic and antiinflammatory agents; u Hardman J., Gilman A., Limbird L.E.: Goodman & Gilman,s The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. Ninth edition. Mc Graw-hill Companies, Health proffessions division, New York, 1996, pp. 617-1484

- Doctor J.N., Slater M.A., Atkinson J.H.: The descriptor differential scale of pain

- intensity: an evaluation of item and scale properties. Pain, 1995; 35: 251-260.

- Cenić D., Lekić D.: Patofiziologija bola. Naučna monografija. Medicinska knjiga, Beograd, 1994, pp. 13-42.

- Jovanović G., Burić N.: Komparativna analiza intenziteta doživljenog postoperativnog bola merenog pomoću Vizuelno analogne skale, Verbal rejting skale i Skale primenjene analgetske terapije. Acta Stomat. Naissi, 2002; 39-40:39-41.

- Kućer Z., Todorović Lj.:Memorija akutnog bola posle hirurškog vađenja impaktiranih donjih umnjaka. Stom. Glas. S., 1999; 46:19-22.

- Gillam D.G., Newman H.N.: Assessment of pain in cervical dentinal sensitivity studies. J. Clin. Periodontol., 1993; 20: 383-394.

- Astuti R., Pasero R.: Pain management. Postoperative pain management in the eldery patient. Adis international, Chester, 1994, pp. 4-14.

- Ohnhaus E.E., Adler R.: Methodological problems in the measurement of pain: A comparison between the werbal rating scale and the visual analogue scale. Pain, 1975; 1: 379-384.

- Seymour R.A., Charlton J.E., Phillips M.E.: An evaluation of dental pain using visual analoque scales and the McGill Pain Qestionnarie. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., 1983; 41: 643-648.

- Seymour R.A., Simpson J.M., Charlton J.E., Phillips M.E.: An evaluation of length and end-phrase of visual analoque scales in dental pain. Pain, 1985; 21: 177-185.

- Sisk A.L., Grover B., Steflik D.E.: Long-term memory of acute postsurgical pain. J. Oral Maxillogac. Surg., 1991; 49: 353-358.

- Heft M.W., Parker S.R.: An experimental basis for revising the graphic rating scale for pain. Pain, 1984; 19: 153-161.

- Gamulin S., Marušić M.: Patofiziološka podloga boli u Gamulin S., Marušić M., Krvavica S.: Patofiziologija. JUMENA, Zagreb, 1990, pp. 449-465.

- Seymour R.A., Walton J.G.: Pain control after third molar surgery. Int. J. Oral Surg., 1984; 13: 457-485.

Zvonko Kućer, D.D.S., MSD, oral surgeon

Clinic of Dentistry,

52 Braće Tasković street

Niš, Serbia,

Serbia and Montenegro

e-mail:zkucer@yahoo.com

- Copyright © 2003 by The Editorial Council of The Acta Stomatologica Naissi